Alexander “Dundonnachie” Robertson and the Bridge Toll Riots

Dundonnachie as we know him was born Alexander Robertson on January 1st, 1825. He was born in the Cross House (now the Dunkeld Mortgage house) and was one of six Alexander Robertsons’ in Dunkeld at the time. At the age of sixteen, after Studying at the Royal School of Dunkeld, Dundonnachie became a Clerk at the Commercial Bank of Scotland in Tay Terrace. Five years after this, he was appointed as the accountant of the commercial bank in Cromarty. In 1853 he began to publish works including one under the pseudonym R Allister entitled Barriers to the National Prosperity of Scotland. After this Dundonnachie became a rather successful businessman with several ventures under his belt. Predominately he was a merchant with a focus on coal, lime, potatoes and timber. Due to his success in these ventures, he built this large house named Dundonnachie in 1859.

Dundondonnachie pictured outside his house ‘Dundonnachie’. Picture undated.

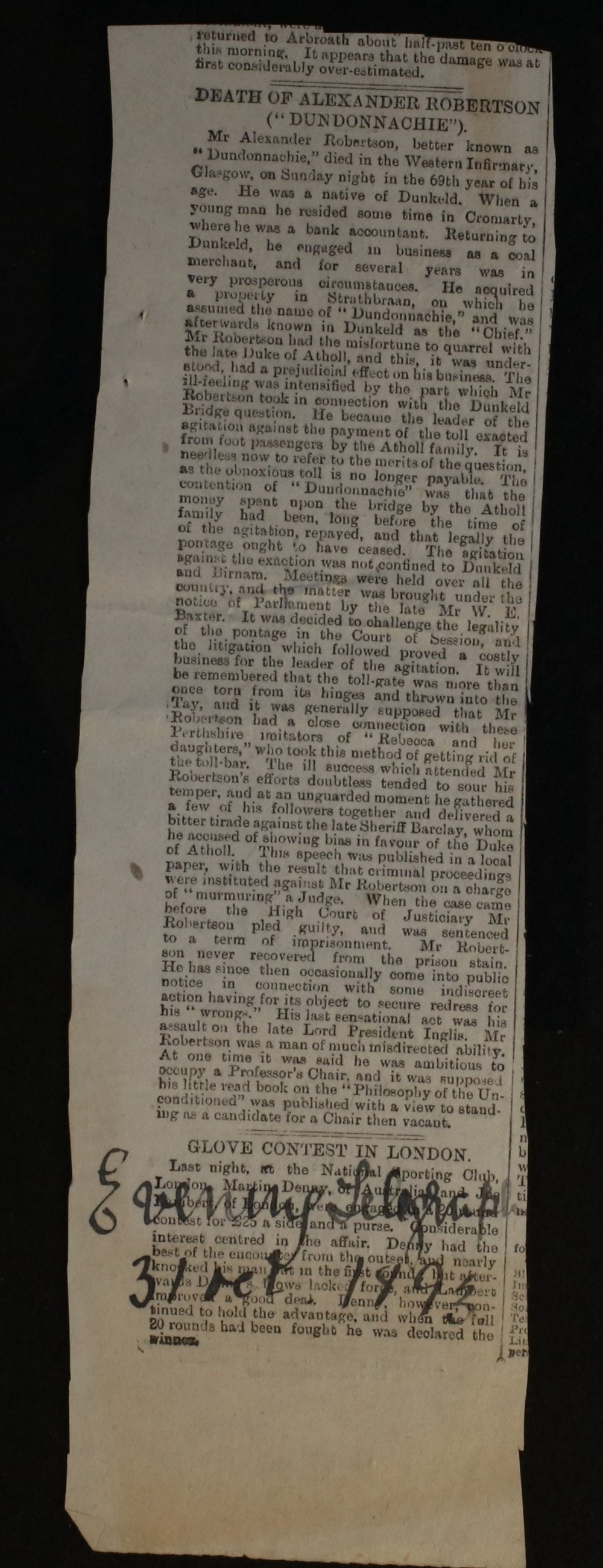

‘Dundonnachie’ House Dunkeld, Built for Alexander “Dundonnachie” Robertson in 1859. Picture undated.

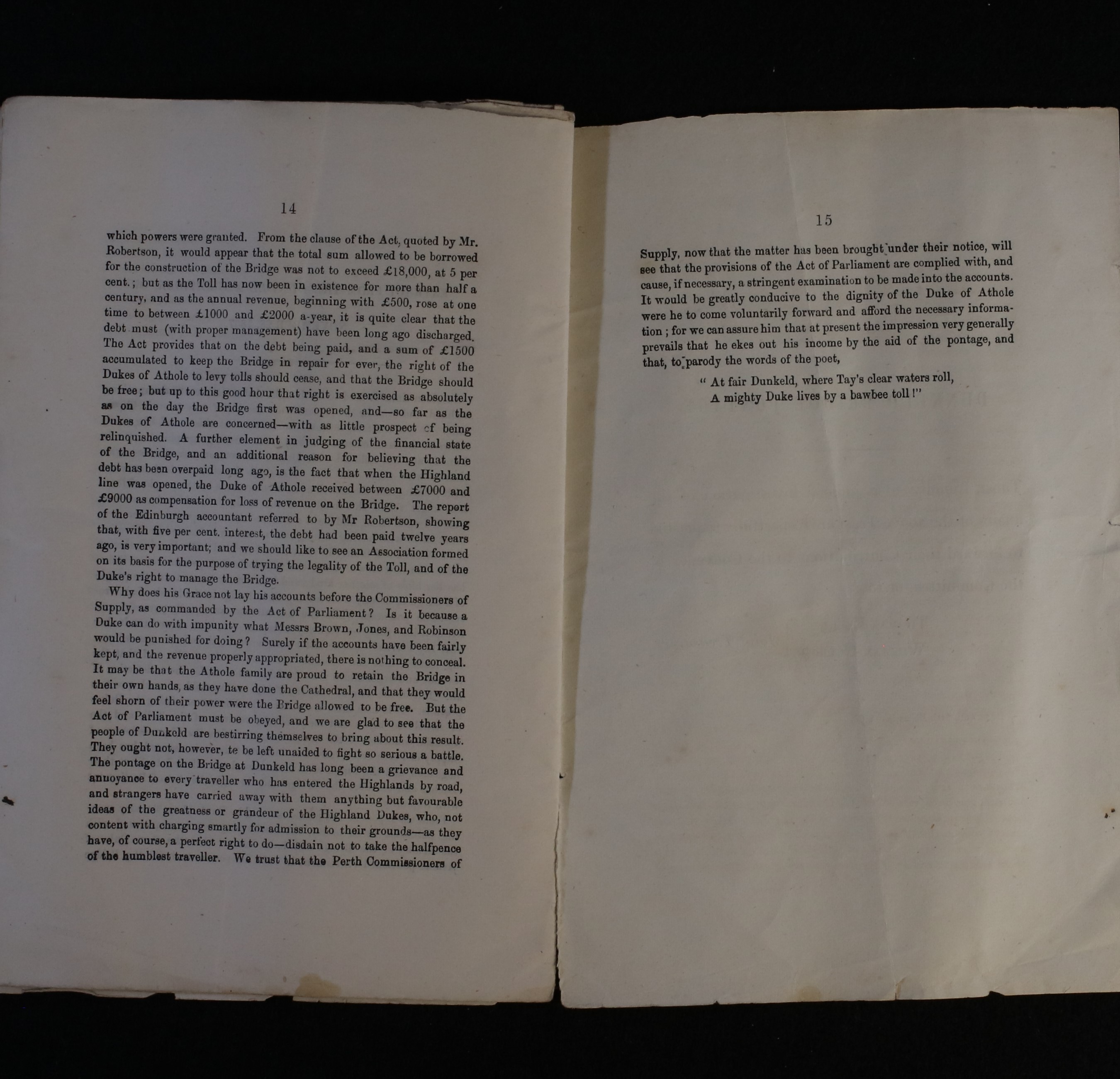

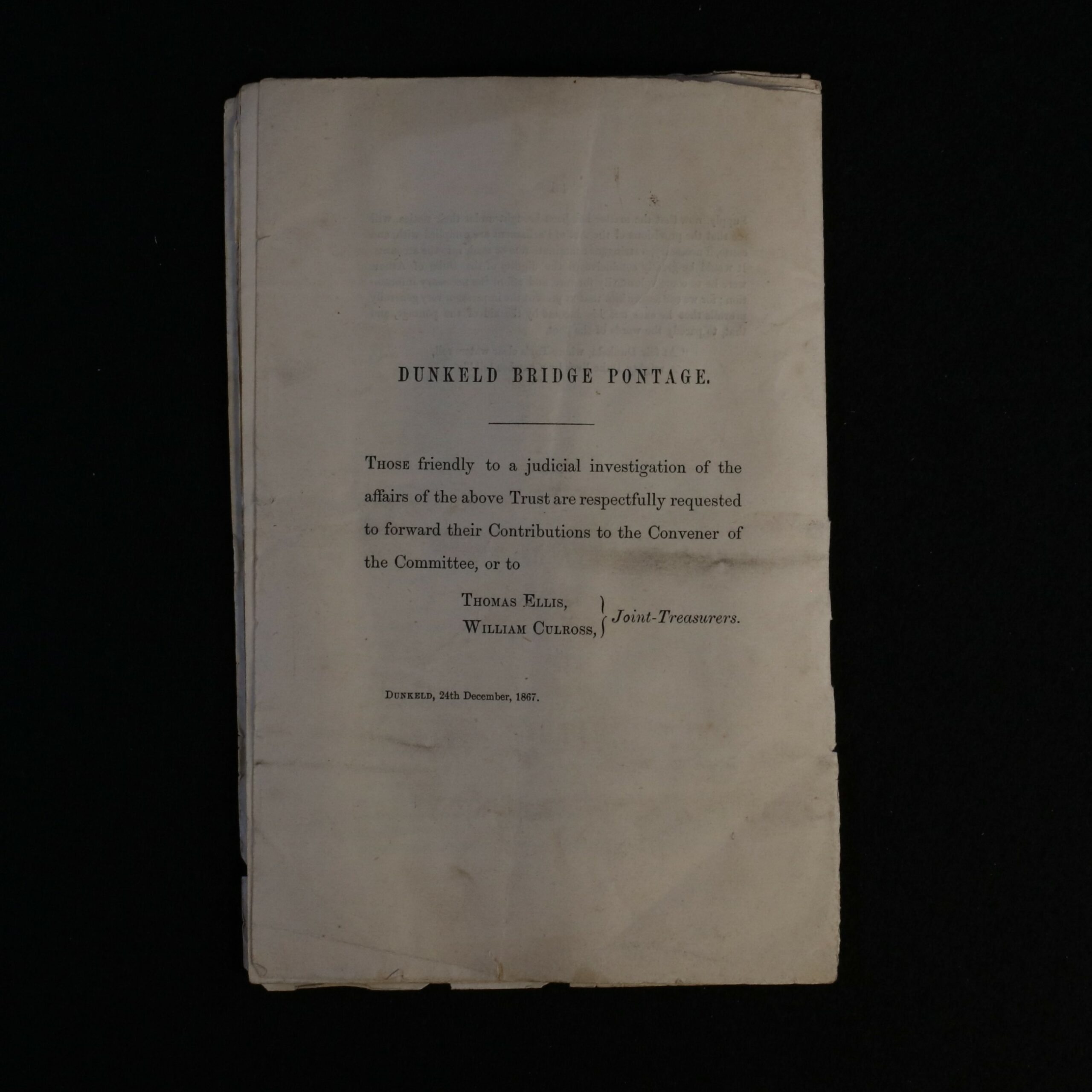

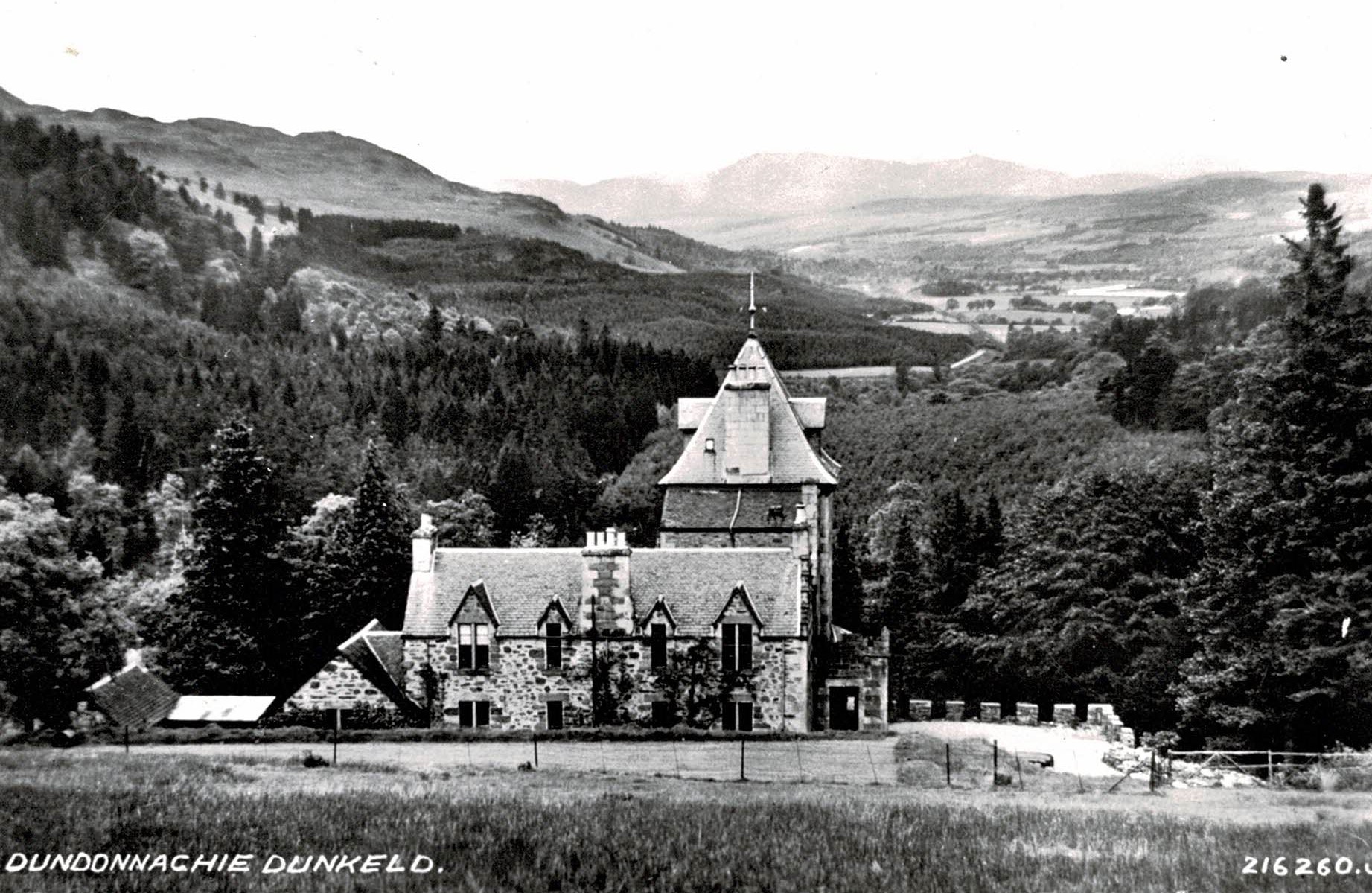

The Dunkeld Bridge was built by Thomas Telford in 1805, opened for Traffic in 1808 and was completed in 1809. This seems rather backwards but final approval was not given for the bridge until after traffic had already begun to cross. The bridge cost a total of around £27,000 despite initial cost estimates being closer to £15,000. This money was paid by the fourth Duke of Atholl who with his heirs, attempted to reclaim it in tolls, eventually leading to the bridge toll riots of Dunkeld. This toll was decreed by the courts and initially the residents of Dunkeld cooperated with it. However,by 1853 there was growing public discontent regarding opinions that the Duke had taken sufficient tolls to pay back his investment in the bridge and was now charging the fees out of personal greed. By 1867 a group had gathered to discuss and protest the Duke’s bridge tolls and Dundonnachie was elected as convener by the group. By February 1868 Dundonnachie’s protests had begun. He walked back and forth across the bridge on the 8th and 10th of February declaring he would not be paying what was legally due in protest against the tolls. On the night of the 10th of February the toll gates were torn from their hinges and thrown into the river Tay. They were later found downstream at Caputh. After this incident the gates were replaced (an action that had to take place several times). Dundonnachie was reported on the night of the tenth by the Toll Collector as standing by the gates “with his bonnet in his hand… begging for a penny for the poor Duke”.

Picture of Dunkeld Bridge. Undated.

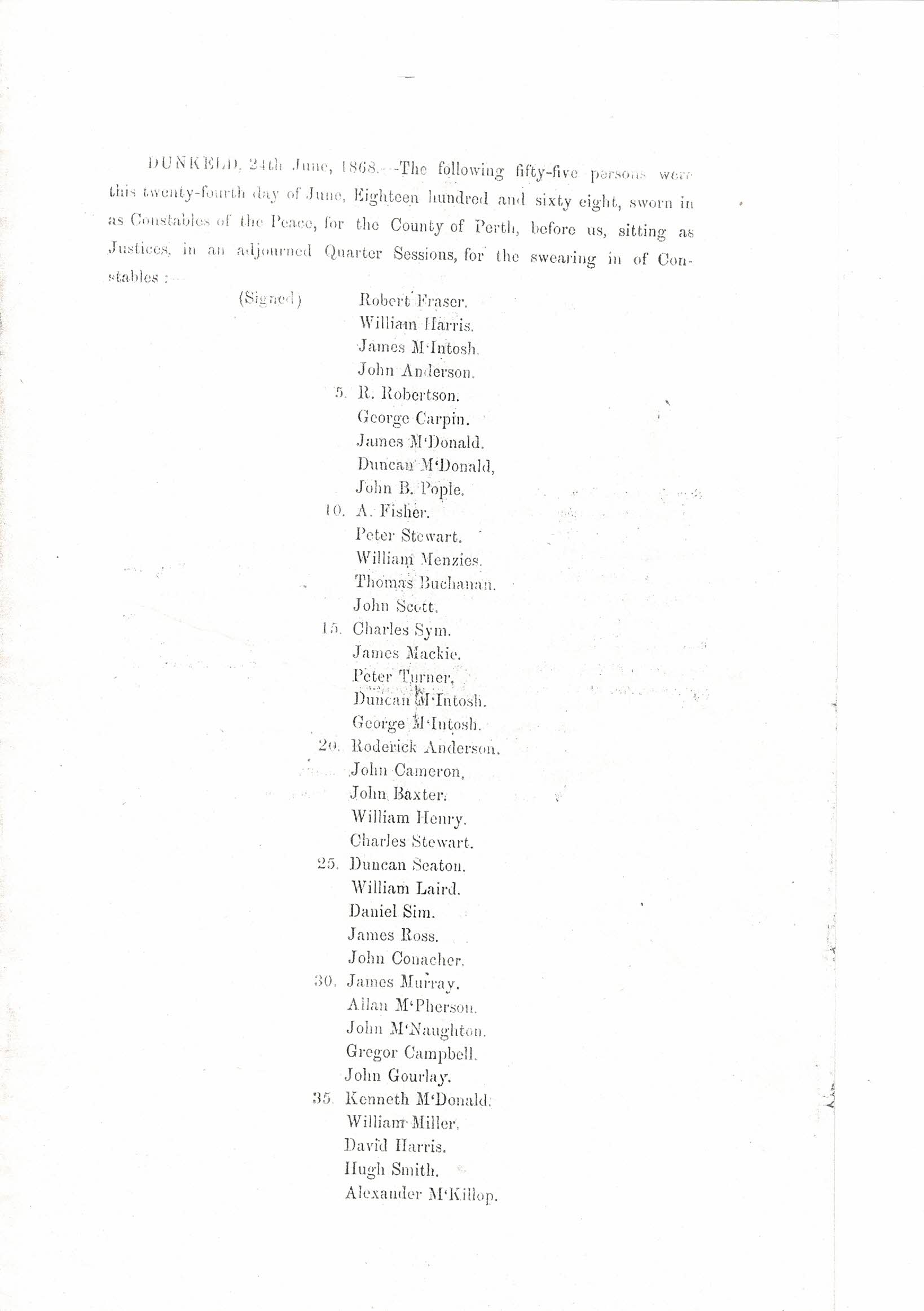

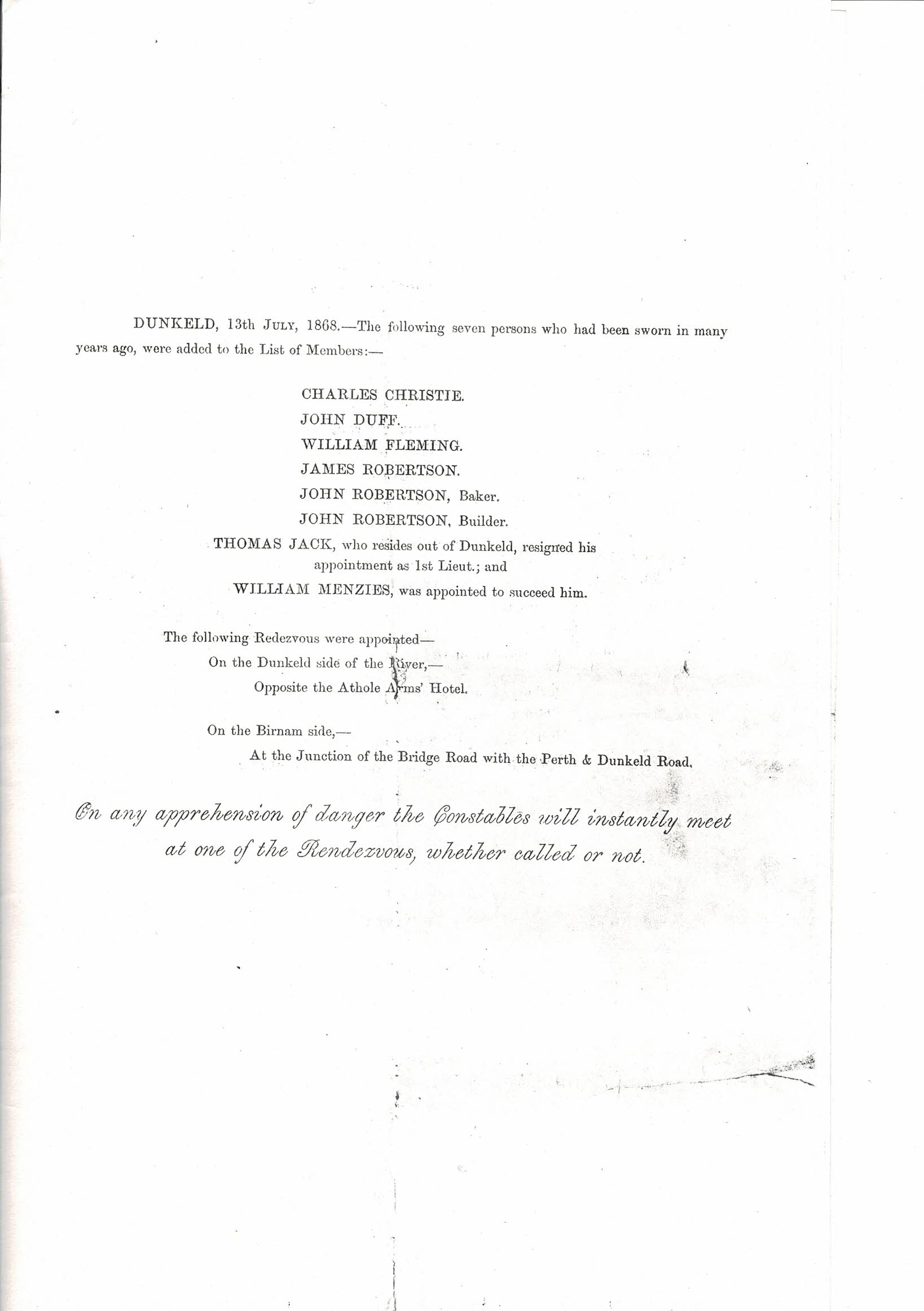

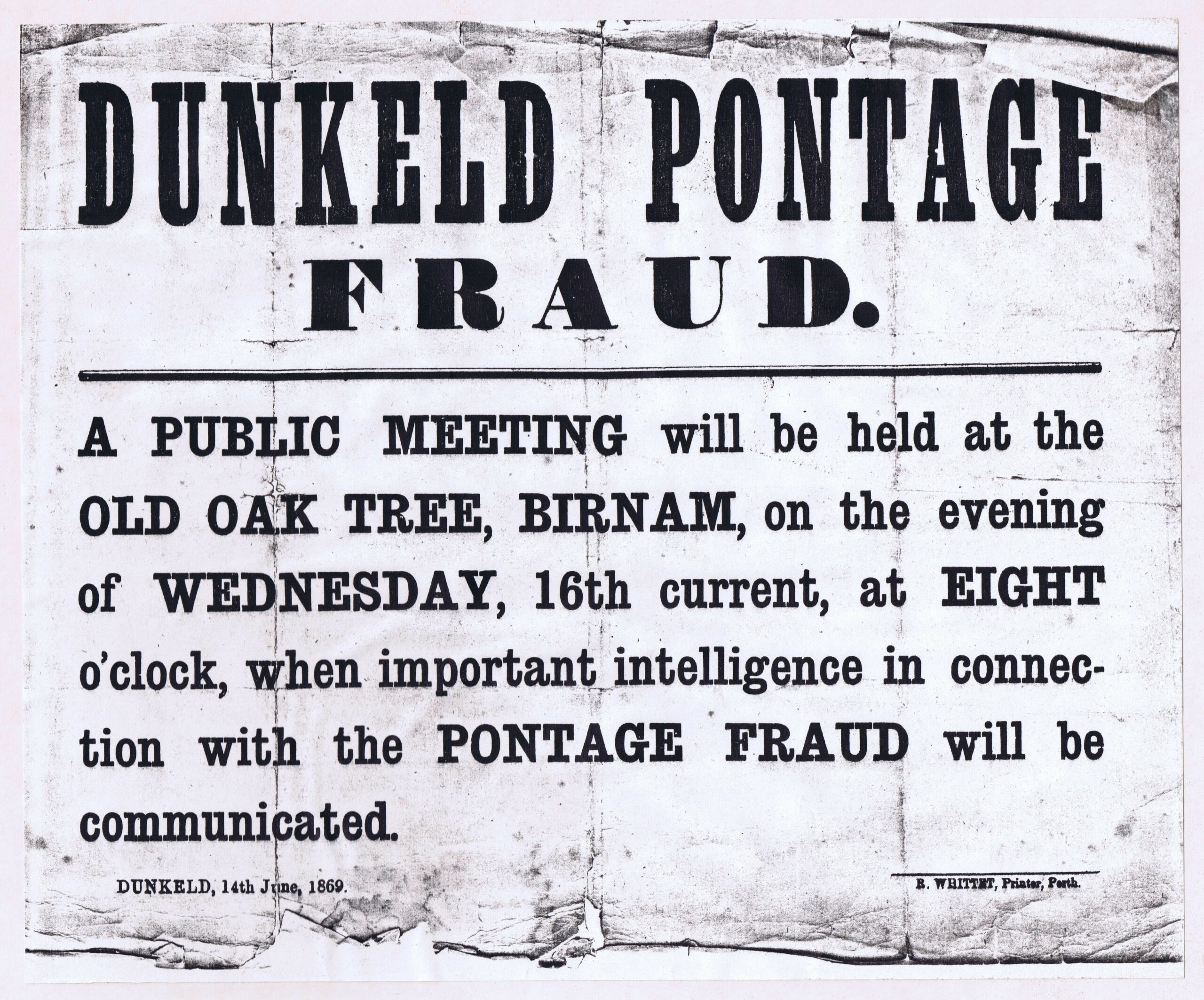

After a lull in events, a meeting was organised on the 16th of June 1868 underneath the Birnam oak. This meeting led to an attack on the gates of the bridge with saws, hammers, axes and more in order to break them down. Onlookers, including the local police, were left flabbergasted and multiple arrests were made as a result of these actions. Fifty-five special constables were hired after this attack. However the peace did not last long. The third attack on the gates occurred on July 7th 1868 in which Dundonnachie attacked the bridge with an axe in one hand and a copy of the Bridge Act in the other. After a dramatic reading of the Bridge Act Dundonnachie started his assault on the toll gates. Despite the dramatic start of the attack, it is reported that Dundonnachie’s axe broke into bits long before the gates met their untimely end. The fourth attack upon the gates was undertaken on July 11th. By 2am all gates and signs and most of the collector’s office had been swiftly removed from the bridge showing even more determination to remove the Duke’s tolls than other attacks.

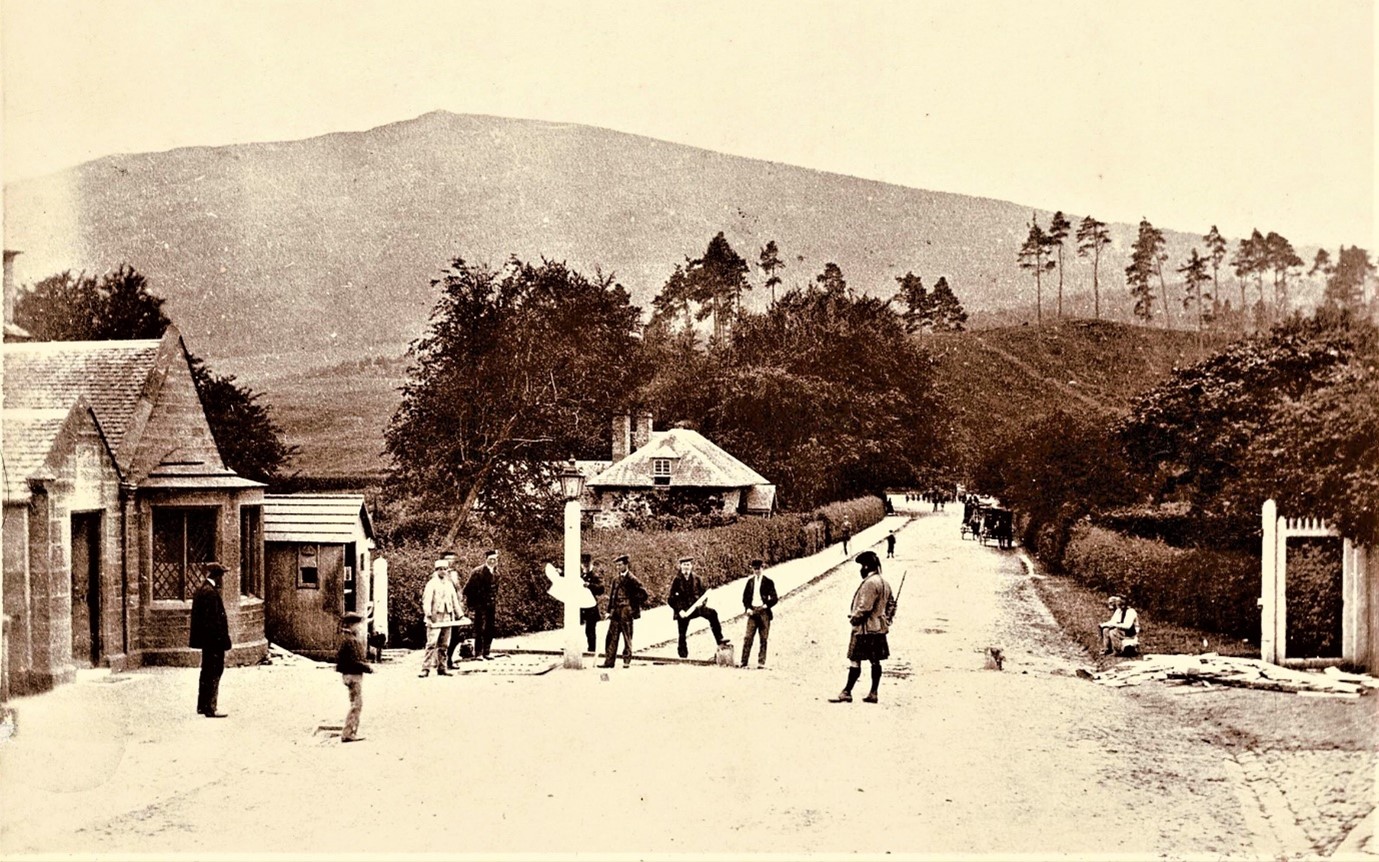

Dundonnachie and other toll rioters pictured in front of the gates on the bridge. picture undated, possibly around 1868.

The poster used to call the protesters to the meeting on the 16th of June 1868.

The violence and thoroughness of the last attack meant that the police and special constables were overwhelmed, resulting in a detachment of the Black Watch arriving in Dunkeld in an attempt to control the locals. This militarisation led to local protests over the bridge, of course without the protestors paying the mandatory toll. Interactions at this point however remained amazingly amicable. During the visit of the Black Watch soldiers, the locals remained friendly and law abiding and for the next 10 years they did not attack the toll gates!

List of Special Constables sworn in due to the Bridge toll riots of Dunkeld on the 24th of June in 1868. There are 55 indivduals named.

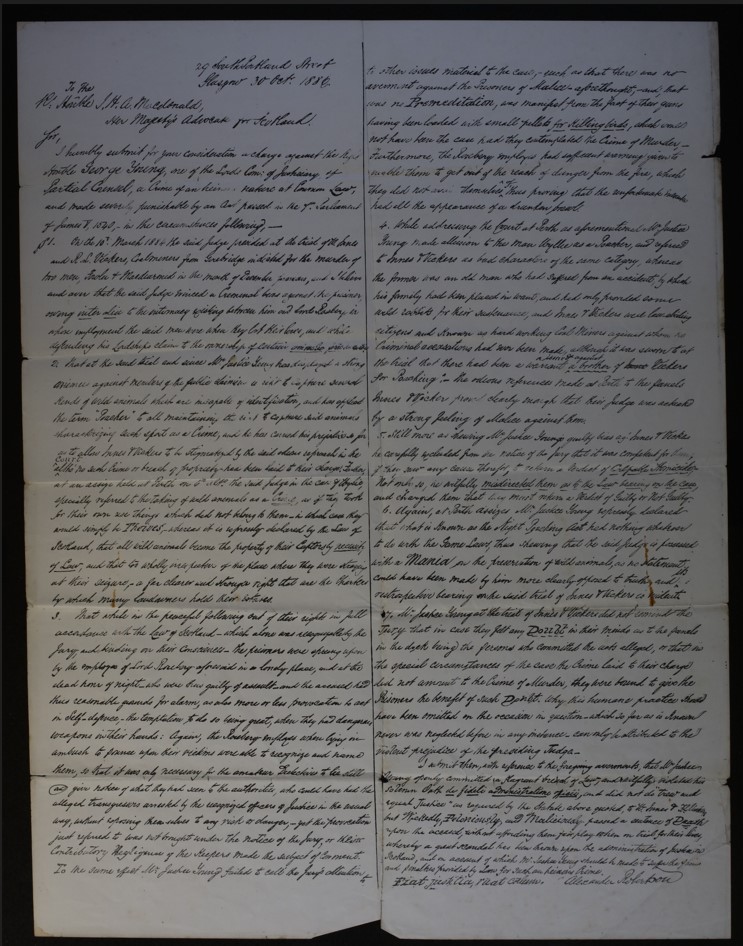

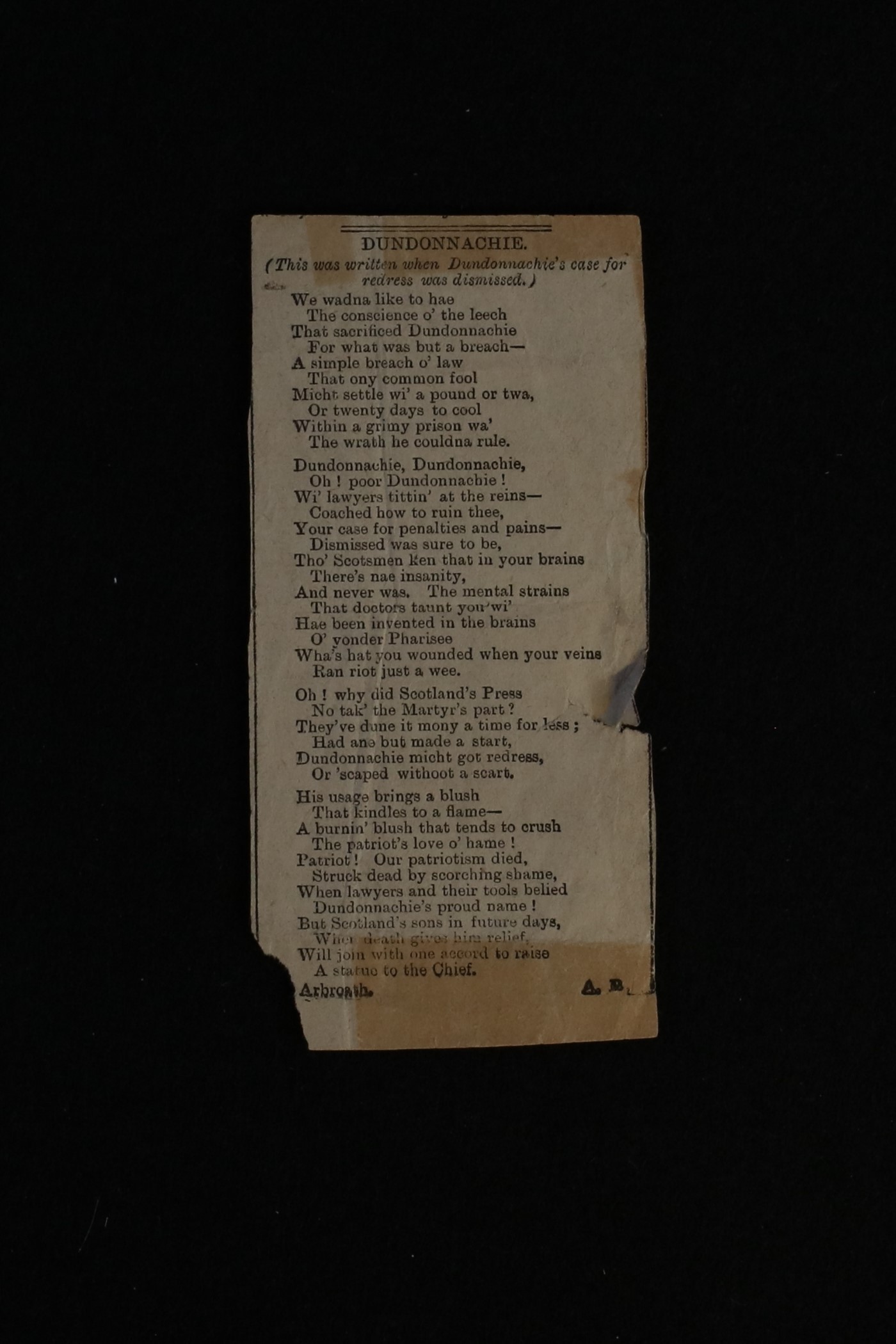

During this period of relative calm Dundonnachie experienced his own personal issues, predominantly a series of court cases against him in which he represented himself. These began on the 18th of July 1868 on a charge of assaulting the toll keeper. He was then charged again in 1870 with “murmuring (criticising) a judge”. He was arrested for this crime on the 12th of January but was not taken to trial and held without bail until the 12th of March. He pleaded guilty and was offered two sentences – one month in prison and a £50 fine or two months imprisonment. He chose the latter offer and held a strong grievance against his sentence as he was sentenced under a law from King James V which had not been enforced for 300 years. This imprisonment caused Dundonnachie to attempt to seek restitution for his grievance for the rest of his life.

Despite having been imprisoned Dundonnachie remained a popular local character and was greeted with a warm welcome upon his return to Dunkeld. However, during his stint in prison, his businesses mostly failed and Dundonnachie fell into bankruptcy which led to the eventual sale of his house (also named Dundonnachie). This in turn led to his move away from Dunkeld and subsequent ventures in London. In 1881 he went to the United States and Canada where he lectured on Scottish life and other similar topics. After this stint abroad he returned to Scotland and moved to Edinburgh, stewing angrily about the injustice of his imprisonment in 1870.

A 3D scan of Dundonnachie’s sporan (As seen pictured at the top of the page). 3D scanned with the kind permission of the Clan Donnachaidh socirty.

On 24th December 1871, the Court of Session, after an appeal to the Inner House, gave their final judgement on the Action raised by Alexander Robertson and others against the Duke of Atholl. The Duke lodged a counter claim, a figure of £65,000 given by the Lord Advocate in the House of Commons. His right to levy tolls was confirmed but his claim was reduced to £18,116. Although the Action failed in its attempt to abolish the toll, it was in other respects a substantial victory for the protestors. Eventually in 1878 the Roads and Bridges (Scotland) Act, which removed the tolls, was passed. The Act came into operation in 1879, and in the middle of the night in May 1879 the Bridge Gates were finally and officially removed. For a number of years they were stored in one of the chambers under the bridge, and then in 1942 were removed in the wartime drive for salvage.

By 1891 Dundonnachie had become completely irrational about his grievance and on the 21st February he assaulted Lord President Inglis on his departure from the Court of Session. Lord Inglis received a blow to the back of the head, knocking his hat off. Dundonnachie was arrested, admitted responsibility, saying he had no intention of causing injury, but wished to draw public attention to his case. The legal process followed, and it became apparent from the beginning that Dundonnachie was suffering from Monomania. On the 30th March, 1891, Dundonnachie was confined on Her Majesty’s pleasure in the Lunatic Wing of Perth Prison.

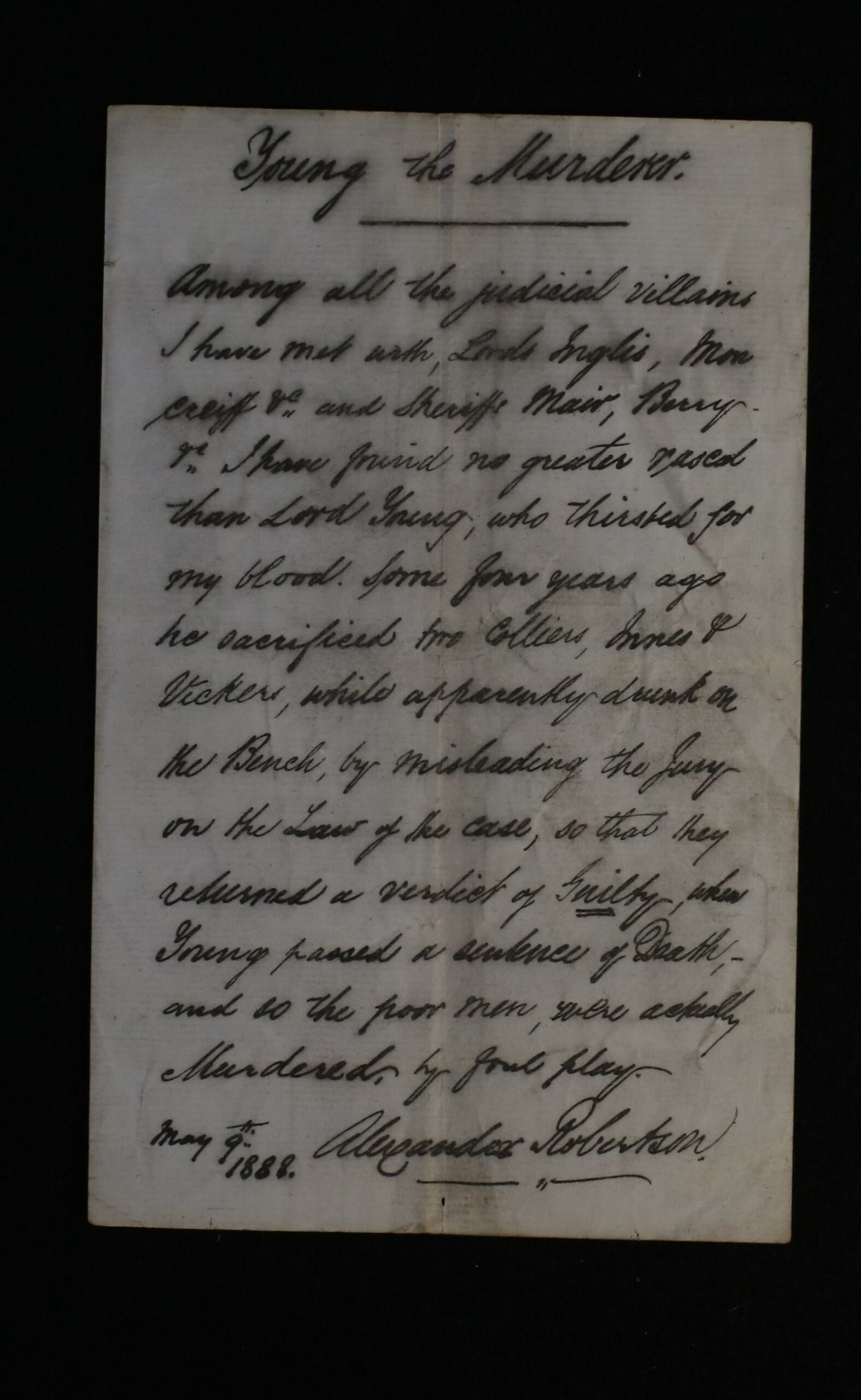

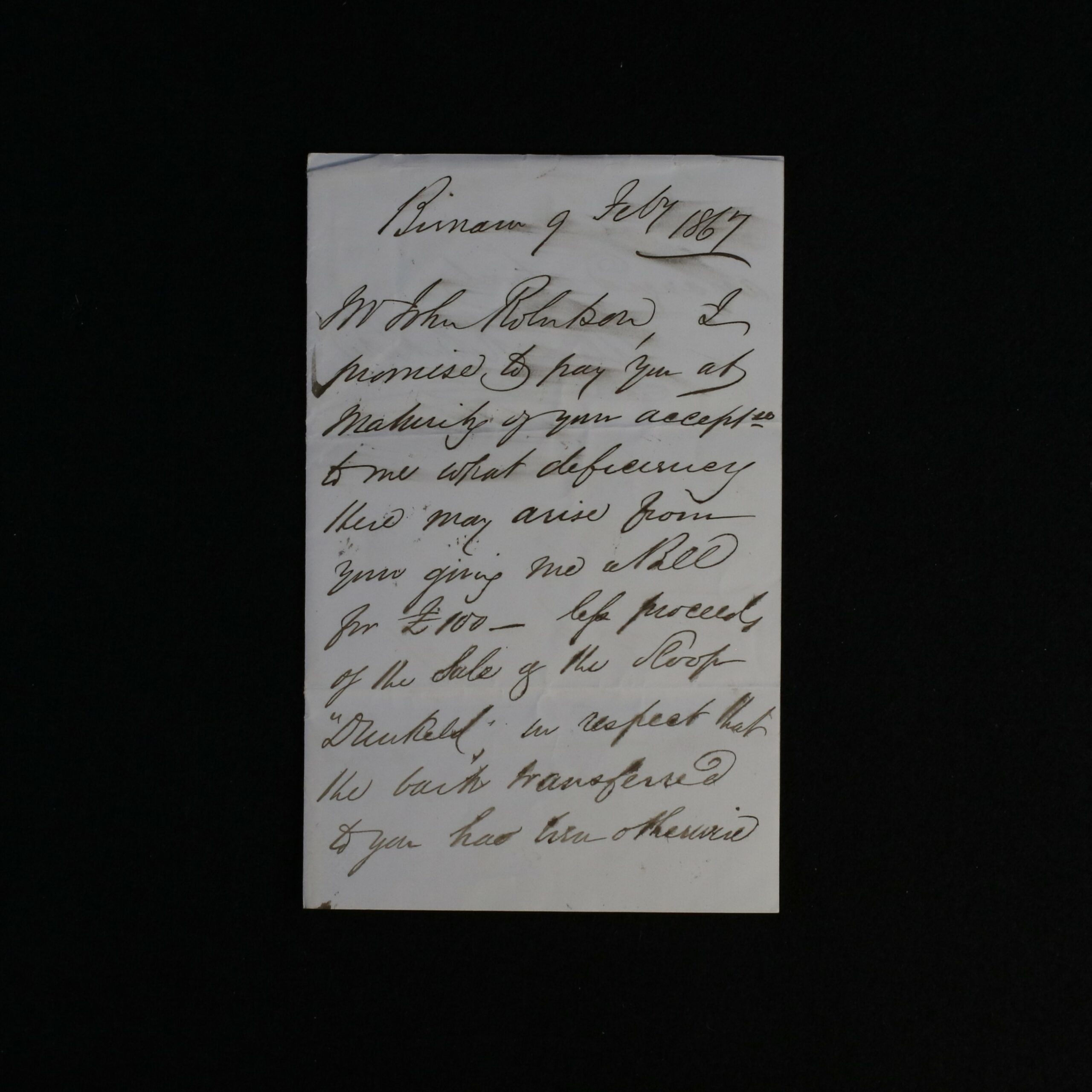

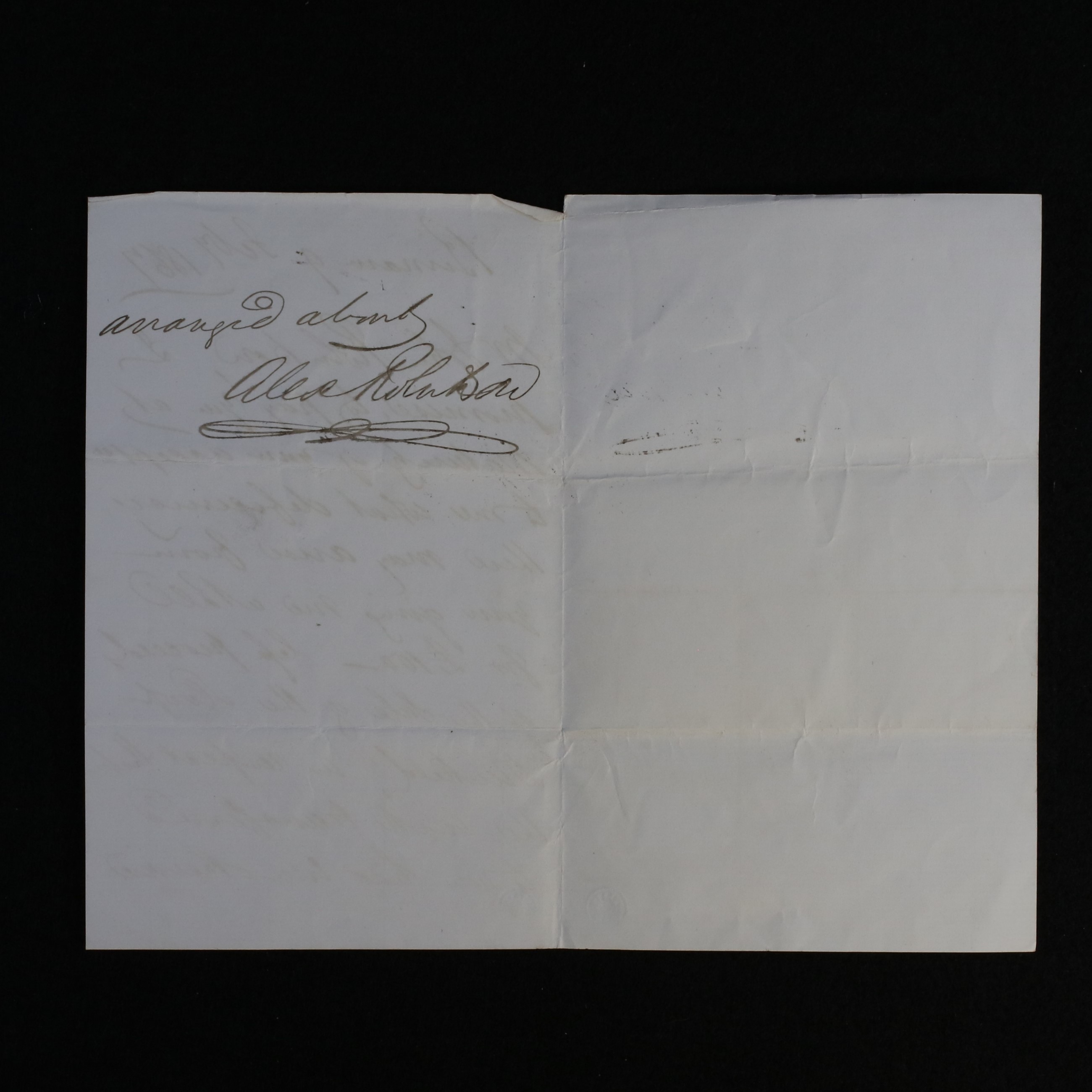

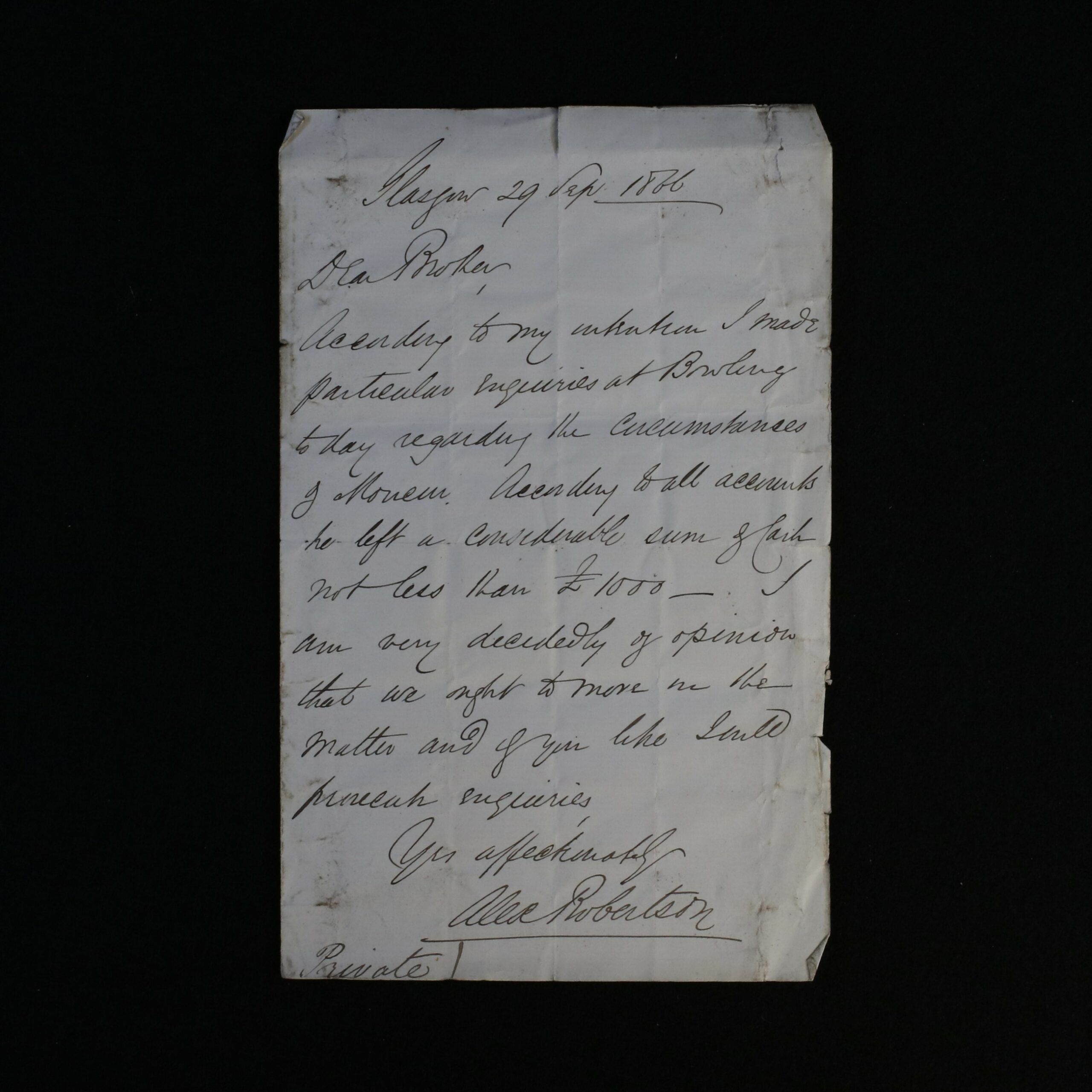

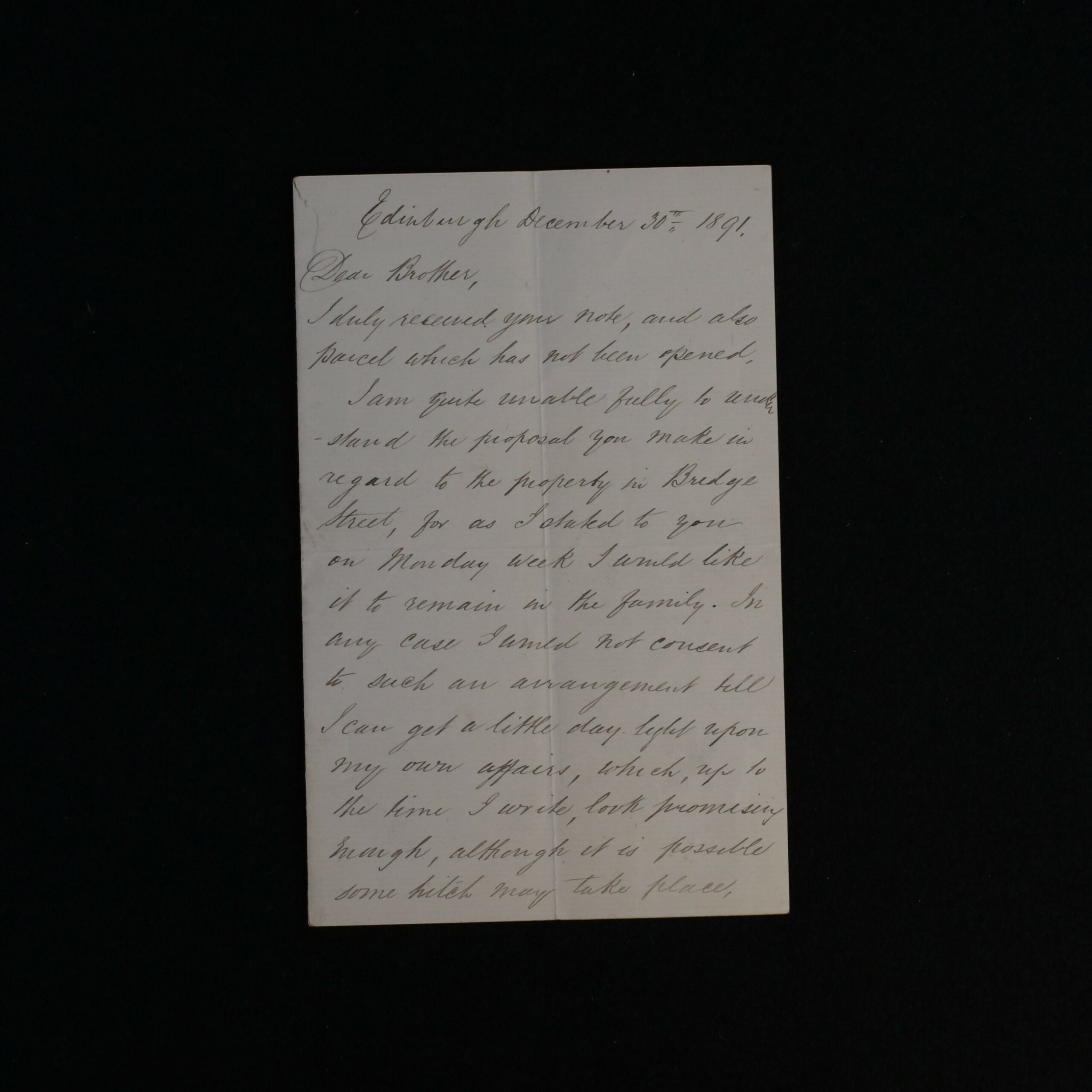

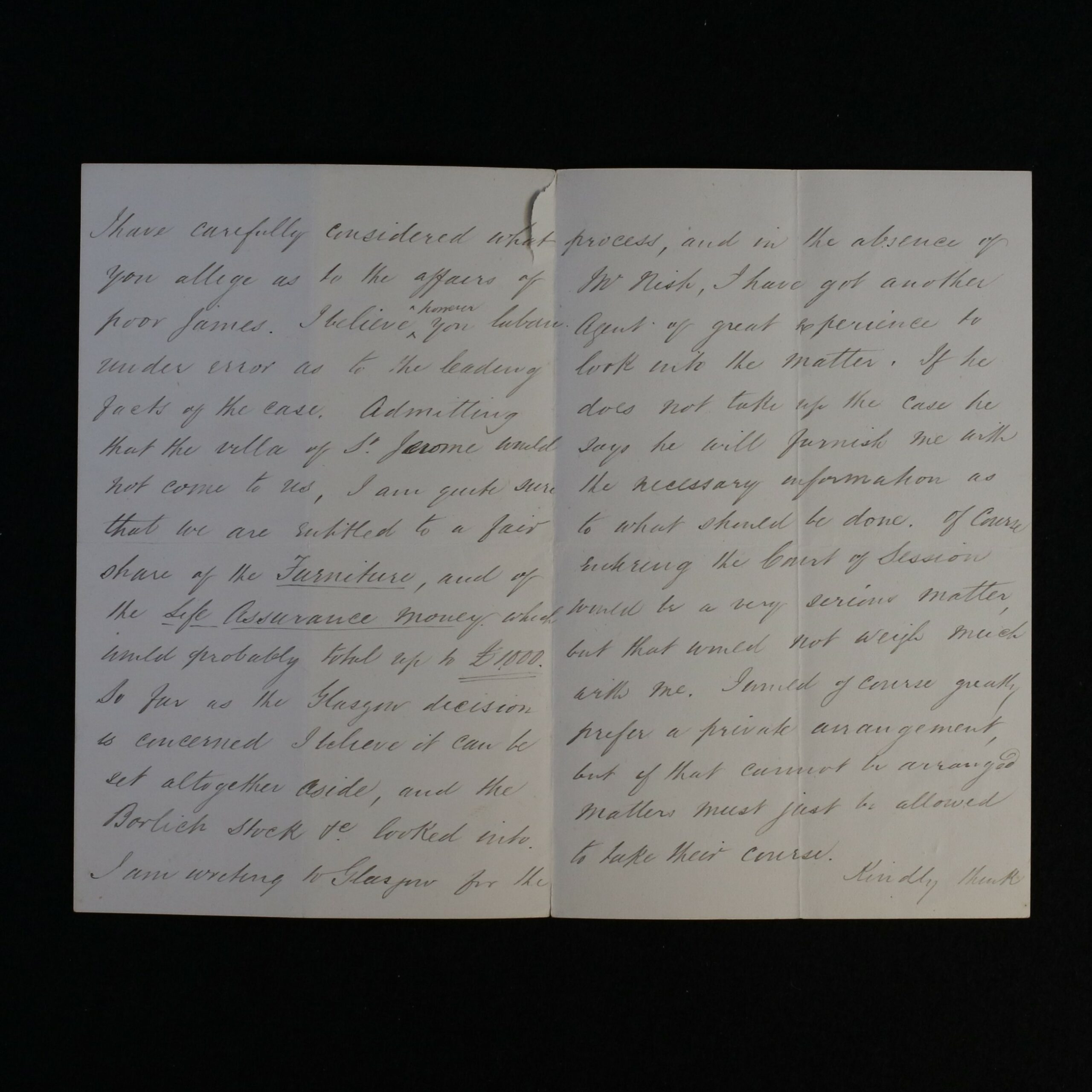

A collection of several handwritten letters by Alexander Robertson, a few of the letters contain some interesting content, including his opinion of some judges!

Dundonnachie died in Glasgow on 29th October, 1893, aged 68 and on the 1st November was buried in the Nave of Dunkeld Cathedral.

Henry Labouchere, M.P., wrote :

“Dundonnachie, when in his prime, was an eloquent speaker and a forcible writer, and , if he had never concerned himself with the Dunkeld Bridge grievance (or even if he had conducted the agitation with more discretion), he would probably have found his way into Parliament. He had the courage to profess and to advocate the most advanced Radical principals at a time when they were exceedingly unfashionable and in a district where all the influence was on the Tory side …..”.

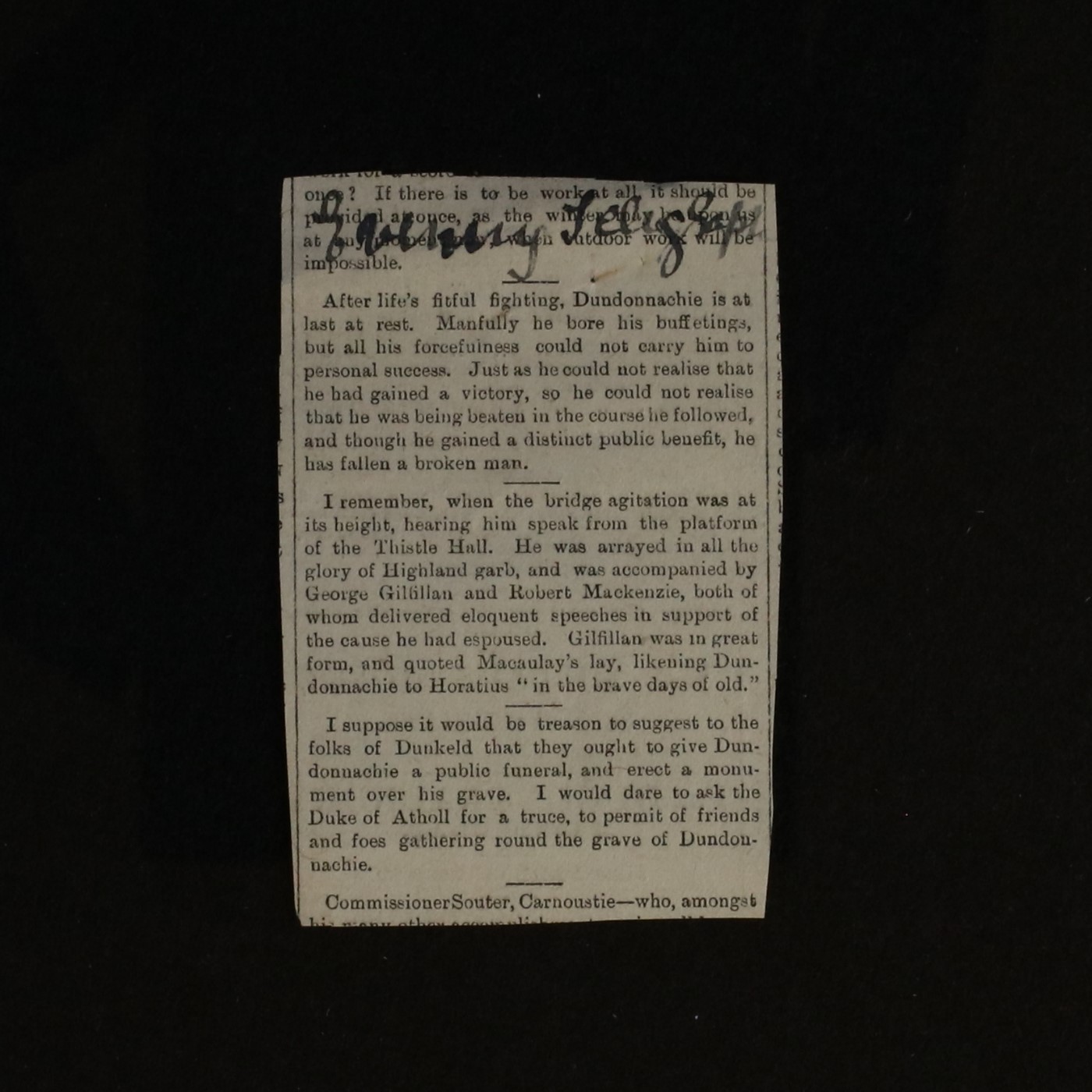

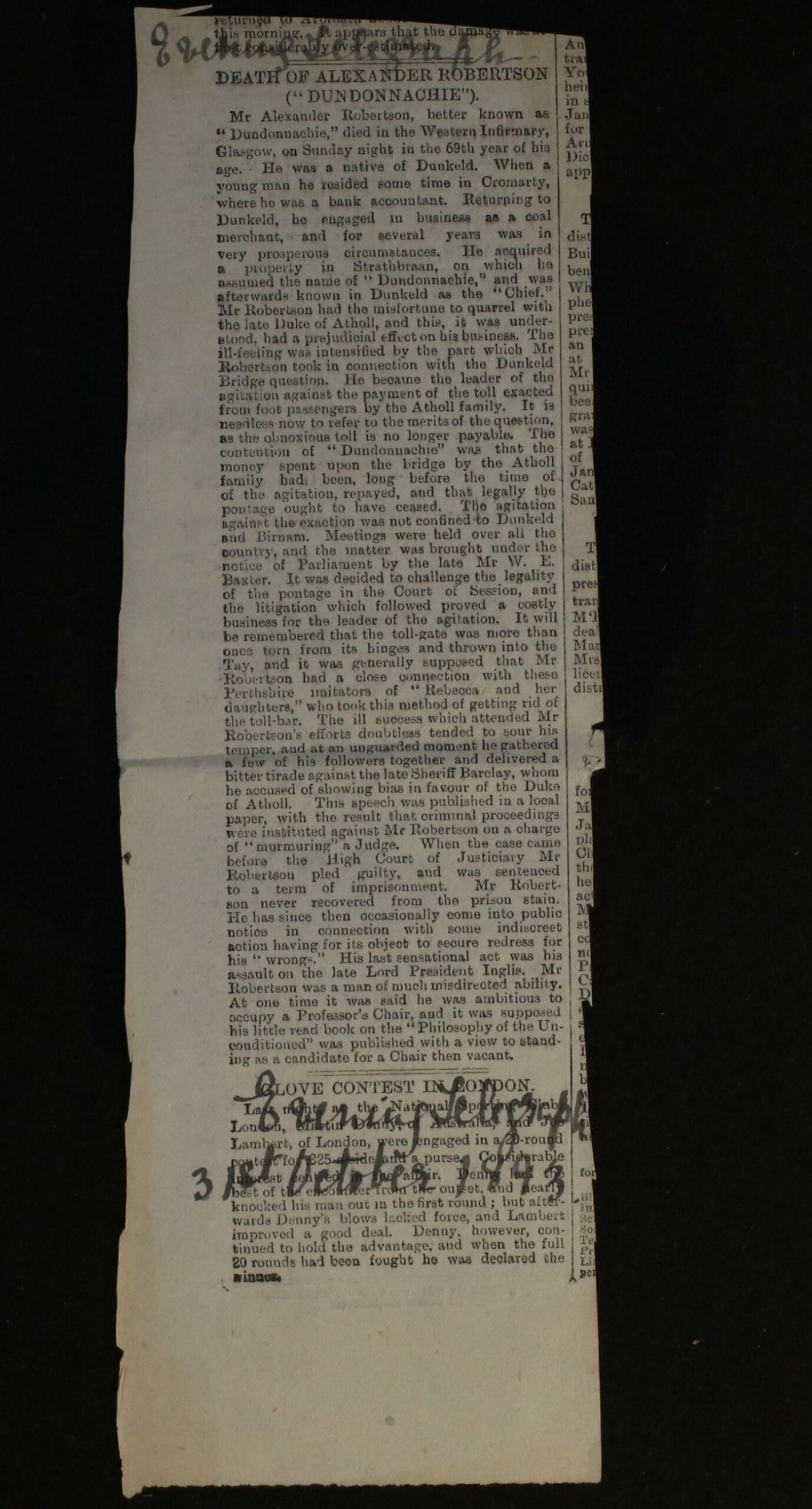

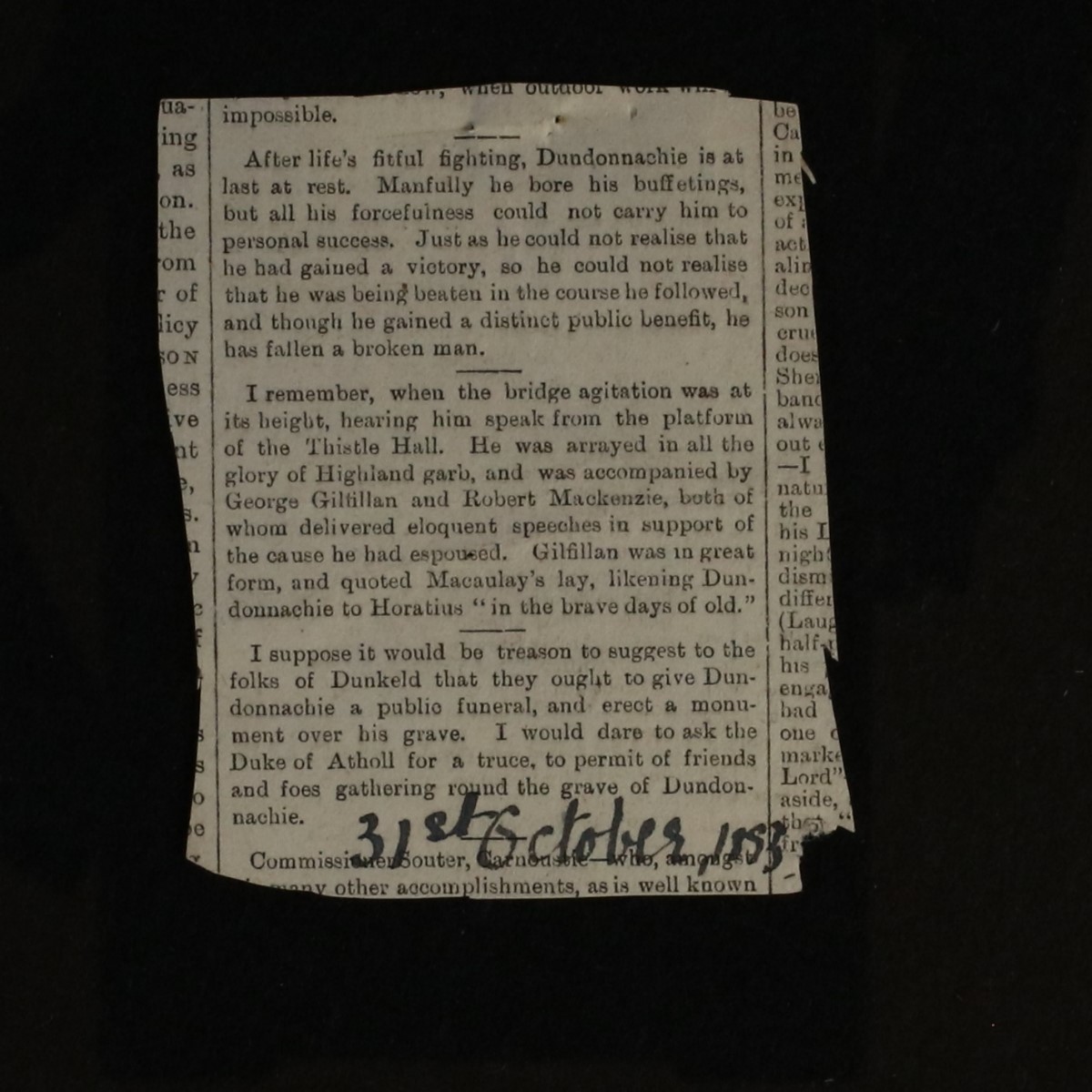

A collection of obituarys for Alexander “Dundonnachie” Robertson. Most are dated 31st of October 1898.

Due to the bridge toll riots Dundonnachie is a well-remembered man within the Dunkeld area, the legacy of the struggle he led against the tolls is well documented – there is a short film available to view animated by Stephen Goodison one of our Kickstarters last year. There is also a children’s book of this film available to purchase from the archive. As well as this Children’s film there was a street theatre production created by Michael, another of our kickstarters.